READ MORE - Study tentatively links flu in pregnancy and autism

you can do something in an instant, which will give you heartache for life

Yet now the Bristol boy is a thoughtful, joyful nine-year-old who attends a mainstream school.

Has he grown out of his condition? New research by a prestigious American university claims that not only is this possible, it’s also common.

A new study in the respected journal Pediatrics reports that up to one third of children diagnosed with autism at a young age no longer display symptoms when they are older.

And the behavioural transformation seen in Josh over the past six years has certainly gone beyond the wildest hopes of his parents.

As a toddler, Josh seemed irretrievably trapped inside his own troubled world.

‘We couldn’t have a cot because he would fling himself against it,’ says Josh’s mother, Renitha, 39, a chartered accountant who teaches at Bristol University.

‘He just slept lying on me. When he was awake he would scream and scream.’

If Renitha wanted something as simple as a shower, her husband, Richard, a lecturer in accounting and finance, also at Bristol University, would have to be on hand.

‘I would pass Josh to Richard and he would have to hold him while he screamed,’ she remembers.

‘There was one day when Josh had tantrum after tantrum, and I was so upset I started crying, and Josh just looked at me without any awareness.

‘I remember thinking: “He will never feel what I’m feeling. He can’t understand emotion”.’

When Josh was three, a health visitor witnessed him having a violent tantrum and referred Josh to specialists at Frenchay hospital, where he underwent twice-weekly diagnostic tests over a six-week period.

‘At the end, the specialists gave me a depressing report explaining that Josh was seriously disabled with autism,’ says Renitha.

Autism is a developmental disorder that affects more than 100,000 children. It is not known what causes it, but it affects a child’s ability to communicate and relate to others.

They are often withdrawn, mute, unable to make eye contact and prone to disturbed sleep and tantrums.

Many never take part in mainstream education and some require full-time care.

Indeed, Josh’s specialists wanted him to be sent to a special school.

‘They did not think he would cope in mainstream school,’ says Renitha.

However, she and her husband decided to reject that advice.

‘We have nothing against special schools, but we thought we would see if mainstream school could work for him first,’ she says.

Nowadays, the difference in Josh would strike outsiders as a massive change.

‘He loves maths and can play Grade 3 pieces on the piano,’ says Renitha.

‘Last year, he made me a beautiful bracelet for Mother’s Day. It made me realise how much things had changed.

‘If anyone is hurt, he will go up to them and ask why and try to give them a cuddle or cheer them up.

'If he is unsure why someone is upset, he will ask questions to try to understand.’

Josh’s transformation is far from unique, according to the Pediatrics study.

The researchers questioned 1,366 parents of children aged 17 and younger who had been previously diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder.

Of these, 453 parents said that their children no longer had the condition and had grown out of it since the age of seven.

The lead researcher, Dr Andrew Zimmerman, from Massachusetts General Hospital for Children, accepts the findings might partly reflect the fact that some of the children may have been misdiagnosed.

But he stresses that these are only a minority, and his results should certainly not be put down to misdiagnosis alone.

‘It is not unusual to see a child start out with more severe autism and then become more moderate and even mild as the years go by,’ he says.

‘A lot of the kids are improving. We don’t know why, except that there’s a lot of mold-ability of the developing brain.’

Dr Zimmerman’s conclusion is backed by previous studies which have suggested that between 3 per cent to 25 per cent of autistic children ‘recover’.

However, it is not a view shared by the UK’s National Autistic Society.

Dr Georgina Gomez-de-la-Cuesta, who leads research at the society, says that although children’s behaviour can improve with intensive support, ‘autism is a lifelong and disabling condition — a child with autism will grow up to be an adult with autism.’

But Professor Simon Baron-Cohen, a psychologist at Cambridge University and one of Britain’s leading experts on autism, agrees that children with the condition can improve significantly.

‘This is not to say the autism goes away or has been cured,’ he says.

‘People with autism are just like anyone else and can be capable of learning.

‘This can change the nature of their brains — because, when any child learns, this process must make changes in their brain. That happens with all of us.’

Is this what happened with Renitha’s son, Josh?

‘Some people say he has grown out of it,’ says Renitha. ‘But they have no idea of the hard work that has been involved.’

Instead, she believes the improvements are a result of her intense efforts to teach Josh to cope with his condition.

She read in a magazine that, in some people with autism, the left and right hemispheres of their brain appear to not ‘connect’ as effectively as people without the condition.

Renitha also read that playing a musical instrument is one of the few activities that activate the left and right hemispheres at the same time.

So Renitha decided to teach Josh the piano when he was only four.

‘To begin with, it was a battle even to get him to sit on the stool,’ she says.

‘But I believe that is one of the things that has helped him develop his brain and to understand the world.’

Josh also had a lot of problems with his coordination and so Renitha spent hours crawling and climbing with him.

‘Josh’s coordination has improved enough for him to start tae kwon-do lessons — although this was not easy,’ says Renitha.

‘He has a very supportive instructor and Josh is now determined to get his black belt one day.

‘I never knew if any of the strategies I used would work. But they were all worth a try. The alternative — Josh being locked in his little world for ever — was far more scary and depressing.’

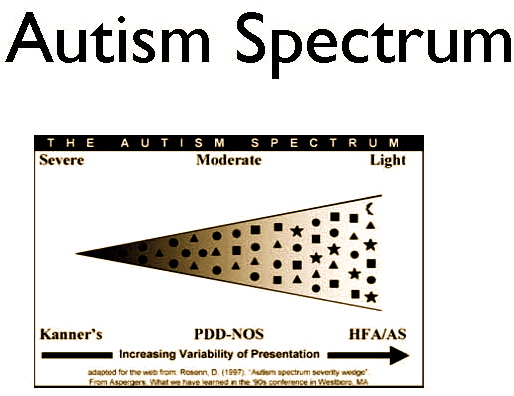

Deborah Fein, a professor of psychology at the University of Connecticut, has studied many autistic children and found that between 10 and 20 per cent can improve so significantly that their diagnosis may change from autism to the less severe form of the condition, Asperger’s syndrome.

But most of the children change only after years of intensive parental support. Sadly, she says, it is not possible to predict which children will improve.

And she cautions that recovery is ‘not a realistic expectation for the majority of kids, but parents should know it can happen’.

Certainly, Josh is very different nowadays. ‘He couldn’t talk. Now he doesn’t stop talking,’ says Renitha. ‘He learnt numbers very quickly and loves maths.’

But Renitha is adamant that Josh will always be autistic. He is in a mainstream school but he needs support to comprehend his lessons, she says: ‘Children don’t grow out of being autistic, but some can learn to live with it.

Autism symptoms

- Repetitive behaviour and resistance to changes in routine

- Obsessions with particular objects or routines

- Poor co-ordination

- Difficulties with fine movement control (especially in Asperger syndrome)

- Absence of normal facial expression and body language

- Lack of eye contact

- Tendency to spend time alone, with very few friends

- Lack of imaginative play

This week, research has emerged that some simple tools could be effective in dealing with autism when implemented at an early age. One of the differences between thought processes in people with autism has to do with visual thinking versus thinking “in words,” and encouraging children at crucial educational stages to “talk things through” in words could help many deal with the effects of autism even as adults, research reveals.

The new data comes from a study in the UK, and British researchers found that while the ability to process thoughts in words exists, many autistic children “don’t always use it in the same way as typically developing people do.” Durham University’s department of psychology lead the study, and researcher David Williams commented on the findings:

The study was published in this month’s Development and Psychopathology Journal, and was conducted at Durham, Bristol and City University London. 15 adults with high-functioning autism and 16 neurotypical adults participated. ( inquisitr.com )“Most people will ‘think in words’ when trying to solve problems, which helps with planning or particularly complicated tasks… Children with autism probably aren’t doing this thinking in their heads, but are continuing on with a visual thinking strategy… So this is the time, at around six or seven years old, that these teaching methods would be most helpful.”